Texts from classical antiquity and popular contemporary stories both tout the notion of the heroine. This is understandable, and as a literary archetype, the female hero is completely legitimate. From time to time, humanity kicks out a woman who is both willing and uniquely qualified to solve some social problem. Such women are heroines, thus the promotion of the heroic ideal understandable, even to a hateful misogynist like me.

I was re-reading Aeneid over the past few days, in anticipation of writing an article about the political future of the United States, when I had a much more interesting epiphany. This week’s conspiracy theory involves feminists using mass-media to subvert the heroine archetype into a promotion of lesbianism, promiscuity, and degeneracy.

One go-to example is my generation’s fictional pop-culture heroine, depicted in Xena: Warrior Princess. For those who were lucky enough to miss this farce, it was a low-budget tee-vee show that came out in the 1990s, and Xena rapidly became the icon for my generation’s yougogrrrlz.

While I never followed the program in my youth, I am familiar with some of the characters. As part of a quick brush-up, I figured I would do some background reading about the history and development of the television drama, and what I found confirmed my every suspicion.

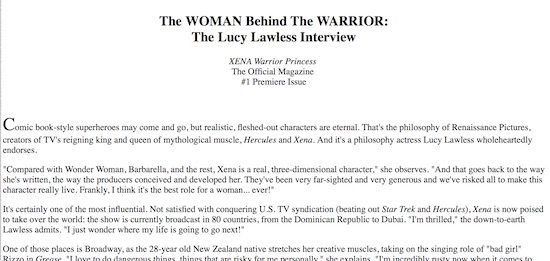

The blocked quotes are all from Wikipedia’s summary of Lucy Lawless, the actress who played the protagonist Xena:

In 1994, Lawless appeared in Hercules and the Amazon Women, a Pacific Renaissance Pictures made-for-television film that became the television pilot for Hercules: The Legendary Journeys. In that episode, she played a man-hating Amazon named Lysia. She went on to play another character, Lyla, in the first-season episode “As Darkness Falls.”

A “man-hating Amazon” is an interesting character to appear in a program targeting young people. In any case, Hercules and the Amazon Women was successful as a pilot, not for launching a tee-vee program about Hercules, but for taking a bit-part and elevating it into the lead.

Lawless received her best-known role when she was asked to play a heroic warrior woman named Xena in the episode “The Warrior Princess,” which aired in March 1995 (R. J. Stewart, one of Pacific Renaissance Pictures’s in-house writers, dramatised the teleplay from a story that Robert G. “Rob” Tapert commissioned John Schulian to write). The character proved to be very successful among fans of the show.

Vanessa Angel was originally cast in the role, but she fell ill and was unable to travel to New Zealand for shooting. To differentiate between Xena and the similar Lysia, Lawless’ hair, previously an ash blonde, was dyed black. She also wore a much darker costume. Lawless subsequently returned as Xena in two more episodes of the first season of Hercules, which portrayed her turn from villainess to a good, heroic character.

So, Lawless’ “Xena” character went from being an evil, man-hating Amazon, to a good, man-hating Amazon.

Lucy Lawless gave an interview about a character she played to some of her fans, in which she described her role as “a real, three-dimensional character… the best role for a woman… ever!”

Part of my interest in the program is the memory of my own reaction to its gradual slide into degeneracy. It seems like I watched it as a kid with waning enthusiasm. Even as the tits-and-ass appeal of it increased, the stupidity of the story and the numerous plot holes kept me from ever getting into it. Moreover, it seemed to have an increasing amount of filthy degeneracy as the series progressed, to the point that any legitimate interest in the characters became impossible.

Am I a biased observer? Lawless herself is a married mother of at least one kid. Even so, she has gone on record stating that she was promoting a degenerate lezbo lifestyle with her role in the series, e.g.:

Xena’s ambiguous romantic relationship with travelling companion Gabrielle (Renee O’Connor) led to Lawless becoming a lesbian icon, a role she has said she’s proud of. She has said that during the years she was playing the role, she had been undecided on the nature of the relationship, but in a 2003 interview with Lesbian News magazine, she said that after viewing the series finale, she had come to see Xena and Gabrielle’s relationship as definitely gay, adding “they’re married, man.”

This reputation became cemented after her “graphic lesbian sex scenes” in Spartacus: Gods of the Arena. She has appeared at gay pride events such as the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras.

In fact, the show did such a great job encouraging young people to adopt perverse lifestyles that she got all manner of honors and awards from fag and dyke organizations.

For her strong support of LGBT rights, including her public support for same-sex marriage, in 2017 Lawless was given the Star 100–Ally of the Year award at the Australian LGBTI Awards ceremony.

I don’t think Xena: Warrior Princess was anomalous. We can see the same feminist pattern writ large in any number of contemporary literary and cinematic situations. If I could codify my conspiracy theory, it’d be something like this:

- Adoption of a legitimate archetype (like the literary heroine) and casting the specific character as a goodlookin’ man-basher.

- Gradual replacement of a coherent story with endless, fractal examples of applied feminism and similar hatred.

- Re-casting the the general archetype as actually standing for feminist ideology.

Men are naturally attracted to what might be called “alpha females,” and the heroine is a token of this type. By getting young boys and men attracted to a character which at first seems semi-normal, but which increasingly promotes degeneracy and insanity, feminists succeed not only in promoting their cause-du-jour, but also in sullying the countless examples of this type that came before. This increases the sense of hopelessness in both men and women, as the viewer is forcibly deracinated from noble ideas via the medium of a filthy bulldyke, shaking her ass on the television.