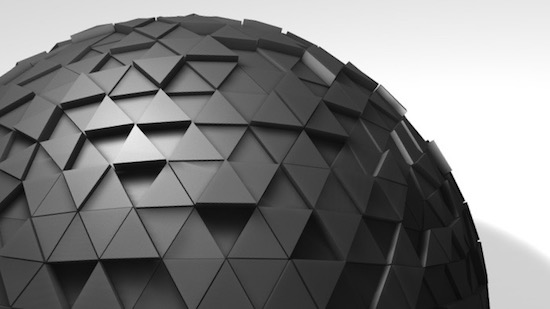

I just got done with Peter Sloterdijk’s book Bubbles, which is the first huge tome in a trilogy entitled Spheres, that, when taken together, will probably compose the author’s magnum opus.

While I’d never call myself a philosopher, I have become competent at reading philosophy, thanks to bothering people who are smarter than I am, while on the clock. Sloterdijk is a philosopher. He’s in residence at Art and Design University, Karlsruhe (Germany). He also hosts a popular television talk show, where he has featured guests as diverse as Paul Virilio and Slavoj Žižek. It’s illustrative to note the difference between European and American tee-vee audiences by this fact alone. I can’t even find middlebrow stuff on pay tee-vee here.

Sloterdijk’s main point in this book is strangely relevant to the ‘sphere (sorry for the pun). It’s a clumsy segue; but, I’m a huge fan of blogs like The Anarchist Notebook, where there’s a fair bit of philosophical import on offer. The author has lately been critiquing open borders libertarians. Our Questioning comrade writes stuff such as:

Open borders advocates’ argument on immigration and human movement, if applied elsewhere, would hold that drug dealers should be allowed to cook meth in an RV within National Parks because the state has no legitimate authority to enforce those rules because it has no just claim to that land it acquired through coercion and finances through theft. Also, in a libertarian society drug dealing would be legal and so would meth production, so the state has no right to enforce anti-drug laws, either.

(Anarchist Notebook)

Libertarians like the idea of open borders because they think that the border jumpers are, at heart, individuals; and that as individuals are basic to a political system, they can be easily integrated into the system they’re jumping into. Thus we see the philosophical problem at the core of political libertarianism: It is a confusion as to what is basic in the political sphere (sorry, again). Libertarians like to think that the individual is basic, but as Sloterdijk points out, individuals don’t exist. Human beings are born with a sense of longing for communion.

Sloterdijk speculates that we come to the conclusion that we are meant to be together with one other due to the presence of the placenta in the womb. The placenta has its own pulse, distinct from the fetus’, and being flushed through the birth canal (and into the underworld) is the beginning of a psychic separation from which we spend the rest of our lives trying to recover.

(Peter Sloterdijk, Spheres Vol. 1: Bubbles. trans: M. Lowenthal. New York: Semiotext(e), 2011. 343-347)

Thus we find ourselves yearning for our twin, and when we find this person, we instinctively marry and settle down and have children.

(Sloterdijk, 414-419)

This is more important than anyone, these days, is prepared to admit. The basic political unit is the dyad: the two-sphere, the family unit, composed of a man and a woman (sorry faggots). This is what the libertarians get wrong, and this is why they’re destined to endlessly circle-jerk from one failure to another, dreaming of a society in which potheads can drive stoned without a government license, without ever causing any accidents. The libertarian paradise suggests that we can successfully integrate 7 billion African refugees into New Mexico without significant social problems. They’re all individuals, and as such, interchangeable with the legal citizens whose people settled that part of North America, so it’s no big deal.

Society in microcosm is not a single person, it is the relationship between two individuals. Herbert Marcuse noted, way back in the 1950’s, that this relationship transcended sex. He also noted that modern industrialized society found it to be too subversive to allow developing naturally. Marcuse invites a comparison:

compare love-making in a meadow and in an automobile, on a lovers’ walk outside the town walls and on a Manhattan street. In the former cases, the environment partakes of and invites libidinal cathexis and tends to be eroticized. Libido transcends beyond the immediate erotogenic zones a process of nonrepressive sublimation. In contrast, a mechanized environment seems to block such self-transcendence of libido. Impelled in the striving to extend the field of erotic gratification, libido becomes less “polymorphous,” less capable of eroticism beyond localized sexuality, and the latter is intensified.

Thus diminishing erotic and intensifying sexual energy, the technological reality limits the scope of sublimation. It also reduces the need for sublimation. In the mental apparatus, the tension between that which is desired and that which is permitted seems considerably lowered, and the Reality Principle no longer seems to require a sweeping and painful transformation of instinctual needs. The individual must adapt himself to a world which does not seem to demand the denial of his innermost needs: a world which is not essentially hostile.

(Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man. New York: Routledge, 1991. 77-78)

Ultimately, the study of what exists is ontology. We are designed (by God or nature, it doesn’t really matter) to couple up with someone we like, and we construct a dyadic ontology to protect ourselves, primarily from invasive ideas. The status-quo hates this, and has spent enormous amounts of time and money trying to erase this aspect of human nature, largely through ideological nonsense like radical feminism, white nationalism, and political libertarianism. We can take heart in the fact that eventually, our enemies are doomed to fail. We are hard wired to immunize ourselves from these toxic ideas, and our resistance to them begins at birth.

Bermuda is an autonomous territory of the U.K. in the North Atlantic. It’s located about 1000 km due east of South Carolina. Last year, the high court decreed that homos had the “constitutional right” to gay-marry each other.

Bermuda is an autonomous territory of the U.K. in the North Atlantic. It’s located about 1000 km due east of South Carolina. Last year, the high court decreed that homos had the “constitutional right” to gay-marry each other.

Amanda & Eric, Married 2/2013

Amanda & Eric, Married 2/2013